How to Handle a Chaotic Player (Input Stream)

Characters in this game take turns in a global turn order. When it is a character's turn, they take an action that applies its effects immediately, and then tell the turn order how many time units must pass before they will act again. The turn order then picks the character that has the next turn (lowest next action timer), and repeats this process indefinitely.

This is great for keeping track of actor turns, and lends itself nicely to the kind of board game mechanics I enjoy. AI can be paused until it is their turn, and call their logic only when it is time to make a decision, producing a single command for their pawn to execute. However, the player is free to think when it is not their turn, change their mind, and even think a few moves ahead. It would be undesirable to only take a single input when the player's pawn is active in the turn order, so we'll want to queue up at least one action, based on the last input the player has entered.

When I tried this first implementation, I noticed that the game felt unresponsive because it was discarding repeated taps of the move key. If I wanted to move three squares up, I couldn't just mash the W key 3 times without waiting between keypresses. If I didn't wait, one of the inputs would get discarded, since the third input would overwrite the second. The criteria for success here is that player intent has to be translated to the game system, and not requiring that the player time their inputs so that the system is ready for them.

The other problem with this implementation is that moving in the same direction over large distances was frustrating on the heavy keyboard switches I like, so we'll need to take Held button inputs as well. And since this is a Hex-grid based game, if the player wanted to go in a direction that didn't align with one of the 3 hex directions (like left or right), they'd have to hold two buttons.

The last problem is a good case to use Unreal's Advanced Input system, since we can map the key pairs Q/D, W/S, and A/E to 3 input axes, then make Actions for pressing a wait key and an interact key. However, while being similar to the state machines mentioned in the linked article, the Input Contexts themselves can't be used to store gameplay data like the queued actions we want, and aren't quite what we need to solve our input queueing problem.

While writing the code the decode input axes from the input system and translate them into the QRS directions my coordinate system uses, I had an interesting question about how to write code using vector math. Do I write it so it's as elegant and satisfying as possible? Or do I write it so that I can debug it at 1 in the morning after coding for 3 hours after an 8 hour workday and putting my daughter to bed… I'm positing the latter is the superior code for my purposes.

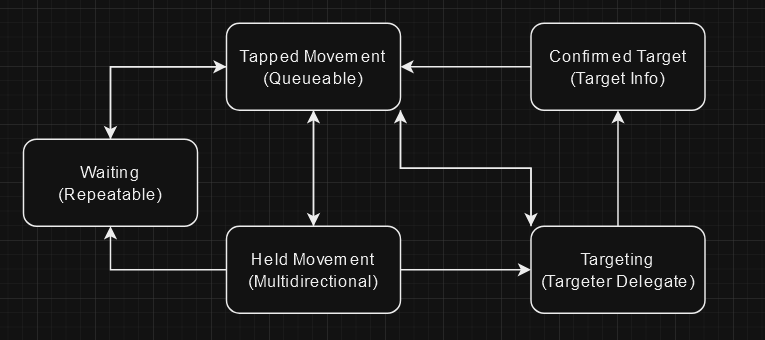

After some experimenting with Unreal's Input Contexts, I decided not to try to be clever and implicitly encode data about the player's intent into the system, and opted for a simple state machine to sit alongside it. The state machine will take inputs from the Input context, which affects which manipulations are possible for our custom Input State Machine. For example, simply pushing on an input context makes it much easier to disable all inputs that might advance the turn order while in menus. When we're ready to start controlling the player's pawn again, their input state will be right where we left it.

The states I settled on were:

There's also a state machine wrapper object to obviate the need for any reference wrangling in the calling code. The state machine takes inputs for:

But most importantly, the states all have a "Get Command" function for the turn order system to consume. The Input State Machine is essentially a buffer of player intents that can be read by the turn order system asynchronously. If there's no player intent to consume, then the turn order waits on them to provide it. In addition to being able to output commands to the Turn system, the input state machine also has outputs for a preview cursor. This is a massive improvement to the feel of tapped movement, since the player can clearly see where they will end up, and can follow the head of their planned movement preview if they are moving through a dangerous environment where they need to watch their step. Without it, players would feel pressured to make only one input at a time if they were standing near the edge of a cliff, for fear of unintentionaly queueing movement that would take them off the edge.